Pevans

HermagorReviewed by Pevans |

Like football (soccer to Americans), Hermagor is a game of two halves, as the saying is. Actually, it’s more a game of two parts since the two sections are anything but equal halves. The first part is a clever and highly competitive auction. The second a logistics/delivery challenge. Emanuele Ornella’s new game for Mind the Move and Rio Grande is excellent stuff and one of my favourite new games of 2006.

Like football (soccer to Americans), Hermagor is a game of two halves, as the saying is. Actually, it’s more a game of two parts since the two sections are anything but equal halves. The first part is a clever and highly competitive auction. The second a logistics/delivery challenge. Emanuele Ornella’s new game for Mind the Move and Rio Grande is excellent stuff and one of my favourite new games of 2006.

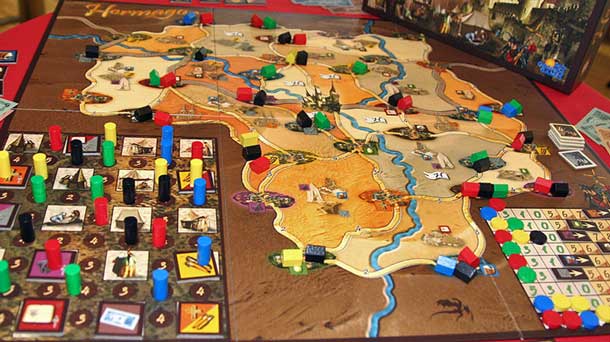

I should start at the beginning, though. Hermagor comes in a chunky box and has lots of nice wooden bits. The main part of the board shows the country and villages around the fictional medieval city of Hermagor. A network of roads between the villages divides the country into areas. Against each village are symbols that show what goods they buy and on each road is the cost of the journey. Each area also has a number of symbols to show what it can produce. The map part of the board fits round two tables. One (the market) is used for the auctions. The other shows the current prices (and values of production buildings) of the eight goods in the game.

Players get wooden pieces in their colour: marker discs for production and cylinders for buyers and their one merchant. Each player also has a stock of houses in their colour, though only a certain number are available each turn. On top of this, there are tiles, price markers for the eight goods and paper money. There’s something rather appealing about a game that has paper money rather than pieces to move along a track. It’s a tactile thing. Or maybe just nostalgia. Money is a major resource in the game and the measure of victory.

Some of the tiles show the number of move/sell actions (3, 4 or 5) that will be available to players each turn. The number and values of these used in the game depend on the number of players. At the start of the game, the appropriate tiles are shuffled. To begin each turn, the top one is turned over and players find out how many actions will be available in the turn. Each takes that number of houses in their colour from the stock.

The turn starts at the market. This is a 4 x 5 grid onto which tiles are placed at random (the number of rows filled depends on the number of players). The tiles generally give the owning player a notional stock of goods – of one or two types. Some also allow them to change the price. A few tiles give special actions, which can be very useful at the right time. In the first part of the turn, players place their buyers, one by one, in the market. They can go on a tile, between two tiles or at the corners of several tiles: each placement costs cash. Once all the buyers have been placed, players get income for the number of buyers they have in each row or column (between the tiles) – the more in a line, the more money. Then each tile goes to the player who has the most buyers around it. Ties are broken in favour of whoever is on top of the tile, then those by the side. Hence, putting a buyer on top of a tile gives most influence, but only over this one tile. While placing buyers at the corners affects several tiles, but has least influence on any one.

The second part of the turn involves the players moving their merchant marker around the road network to ‘sell’ their goods and establish shops. Each move costs the player however much is shown on that section of road. After each move, the player can sell goods where they have arrived and place a house – unless they already have a house there. Selling goods does not mean turning in tiles: players keep them and can sell the same good several times in a turn (in different villages). The sale brings in cash for the seller, according to the current price for that good. Players can opt to move and not sell, in which case they only have to pay half price for the move, but still have to give up a house. Or they can sell at the village they start at, place a house and not move. The number of houses available thus controls how many actions a player can take.

Apart from marking villages players have already sold at, the houses show their progress around the areas. When a player has a house in every village around an area, they get to place a disc on the production side of the price table for one of the goods shown in the area. This brings in some money, which gets smaller as more discs are placed for that good. There’s thus an incentive to be first to establish production for each good. Some areas show an H on a flag: this is an indicator of nobility and allows the player to place a disc on the ‘nobility’ row at the bottom of the price table. Here the values go up as more discs are placed.

The turn ends once players have completed their actions. The tiles go back into the bag, the next action tile turned over and it’s time to visit the market again. After all the turns have been played, players get some bonuses. To start with, there is cash for each row of the production/price table that players have at least one disc on. The amount they receive depends on the price of the good, giving a further incentive for pushing up the price of the good during the game. Each player gets a second bonus according to the number of houses they have in the three sections of the country (bounded by the rivers). It’s the smallest number that matters, giving players an incentive to spread their houses widely across the board. Finally, the player(s) with the most houses on the main road gets a bonus and the player(s) with the fewest loses the same amount. The winner is the player with the most money at the end of the game.

There’s a lot to think about in Hermagor. While you get some cash for placing your buyers, most money comes from selling goods and, particularly, the bonuses for production buildings (discs) at the end of the game. To my mind, the market is the core of the game as, in the second part of the turn, players want to move to villages where they can sell goods. So first they must have the goods. There is thus a premium on planning ahead. Know where you want to go in the second part of the turn and you know what goods to bid for at the market. Though this is also influenced by which tiles are available and what the other players are after. Getting involved in a bidding war is painful and often provides bargains for those not involved.

It’s also worth looking ahead to the end-of-game bonuses, particularly for production discs. Again, identify what you’re after and you know which areas will be useful and thus which goods (and price changes) you need. As always, though, you have to trim the sails of your strategy to the changing winds of tactical opportunity. With its carefully interlocking mechanisms, Hermagor provides a fascinating challenge. And the vagaries of the market make sure it’s different each time you play. I am still learning this game – each time I play it I find more to it. I recommend you get started at once.

Hermagor was designed by Emanuele Ornella and published by Mind the Move (with an English language version from Rio Grande Games). It is a strategy board game for 2-5 players, aged 12+, and takes 90-120 minutes to play.

Pevans rates it 9/10 on his highly subjective scale.

This review was first published in Gamers Alliance Review, Spring 2007.